thomas whately advocated a natural approach to landscape design using what four basic elements?

Urban planning designs settlements, from the smallest towns to the largest cities. Shown here is Hong Kong from Western District overlooking Kowloon, across Victoria Harbour.

Planning theory is the body of scientific concepts, definitions, behavioral relationships, and assumptions that define the body of noesis of urban planning. There are 9 procedural theories of planning that remain the principal theories of planning procedure today: the Rational-Comprehensive arroyo, the Incremental approach, the Transformative Incremental (TI) approach, the Transactive approach, the Communicative arroyo, the Advocacy arroyo, the Equity arroyo, the Radical arroyo, and the Humanist or Phenomenological approach.[1]

Background [edit]

Urban planning can include urban renewal, by adapting urban planning methods to existing cities suffering from decline. Alternatively, it can concern the massive challenges associated with urban growth, particularly in the Global South.[two] All in all, urban planning exists in various forms and addresses many unlike bug.[3] The modernistic origins of urban planning lie in the movement for urban reform that arose as a reaction against the disorder of the industrial city in the mid-19th century. Many of the early on influencers were inspired by anarchism, which was popular in the plow of the 19th and 20th centuries.[4] The new imagined urban form was meant to go hand-in-mitt with a new society, based upon voluntary co-functioning within self-governing communities.[4]

In the late 20th century, the term sustainable development has come to correspond an ideal outcome in the sum of all planning goals.[v] Sustainable compages involves renewable materials and energy sources and is increasing in importance every bit an environmentally friendly solution[6]

Blueprint planning [edit]

Since at least the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, urban planning had generally been assumed to be the physical planning and design of man communities.[seven] Therefore, it was seen every bit related to architecture and ceremonious technology, and thereby to be carried out by such experts.[7] This kind of planning was physicalist and design-orientated, and involved the production of masterplans and blueprints which would prove precisely what the 'terminate-state' of land use should be, similar to architectural and engineering plans.[8] Similarly, the theory of urban planning was mainly interested in visionary planning and design which would demonstrate how the platonic metropolis should be organised spatially.[9]

Germ-free movement [edit]

Although it tin can exist seen as an extension of the sort of civic pragmatism seen in Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah or William Penn's plan for Philadelphia, the roots of the rational planning movement lie in U.k.'s Sanitary movement (1800–1890).[x] During this menstruation, advocates such every bit Charles Booth argued for central organized, elevation-down solutions to the issues of industrializing cities. In keeping with the rise ability of manufacture, the source of the planning say-so in the Germ-free motility included both traditional governmental offices and private development corporations. In London and its surrounding suburbs, cooperation between these two entities created a network of new communities amassed around the expanding track organisation.[11]

Garden urban center move [edit]

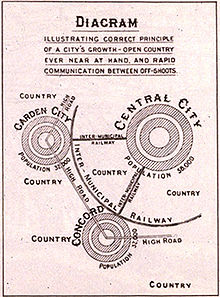

A diagram of Howard's planned Social Urban center.

The Garden city movement was founded by Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928).[12] His ideas were expressed in the book Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898).[13] His influences included Benjamin Walter Richardson, who had published a pamphlet in 1876 calling for low population density, good housing, wide roads, an underground railway and for open infinite; Thomas Spence who had supported mutual ownership of land and the sharing of the rents it would produce; Edward Gibbon Wakefield who had pioneered the idea of colonizing planned communities to house the poor in Adelaide (including starting new cities separated past green belts at a certain point); James Silk Buckingham who had designed a model town with a central place, radial avenues and industry in the periphery; as well equally Alfred Marshall, Peter Kropotkin and the back-to-the-country movement, which had all called for the moving of masses to the countryside.[xiv]

Howards' vision was to combine the best of both the countryside and the city in a new environment called Town-Land.[15] To make this happen, a group of individuals would found a express-dividend company to buy cheap agricultural land, which would and then be adult with investment from manufacturers and housing for the workers.[15] No more than than 32,000 people would be housed in a settlement, spread over 1,000 acres.[15] Effectually it would be a permanent green belt of 5,000 acres, with farms and institutions (such every bit mental institutions) which would benefit from the location.[xvi] Afterwards reaching the limit, a new settlement would be started, connected by an inter-city rail, with the polycentric settlements together forming the "Social City".[16] The lands of the settlements would be jointly owned past the inhabitants, who would use rents received from it to pay off the mortgage necessary to purchase the country and so invest the rest in the community through social security.[17] Actual garden cities were congenital past Howard in Letchworth, Brentham Garden Suburb, and Welwyn Garden Urban center. The motion would also inspire the afterward New towns movement.[18]

Linear city [edit]

Arturo Soria's blueprint concept of the Linear city.

Arturo Soria y Mata'due south thought of the Linear city (1882)[nineteen] replaced the traditional idea of the city as a heart and a periphery with the idea of constructing linear sections of infrastructure - roads, railways, gas, h2o, etc.- along an optimal line and so attaching the other components of the city along the length of this line. As compared to the concentric diagrams of Ebenezer Howard and other in the same menses, Soria's linear city creates the infrastructure for a controlled procedure of expansion that joins one growing urban center to the adjacent in a rational way, instead of letting them both sprawl. The linear metropolis was meant to 'ruralize the city and urbanize the countryside', and to be universally applicable as a ring effectually existing cities, as a strip connecting ii cities, or equally an entirely new linear town across an unurbanized region.[20] The idea was later taken up past Nikolay Alexandrovich Milyutin in the planning circles of the 1920s Soviet Union. The Ciudad Lineal was a practical awarding of the concept.

Regional planning motion [edit]

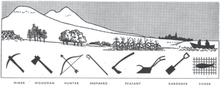

An archetypical example of a Valley Department.

Patrick Geddes (1864-1932) was the founder of regional planning.[21] His principal influences were the geographers Élisée Reclus and Paul Vidal de La Blache, besides equally the sociologist Pierre Guillaume Frédéric le Play.[22] From these he received the idea of the natural region.[23] Co-ordinate to Geddes, planning must offset by surveying such a region by crafting a "Valley Section" which shows the general slope from mountains to the ocean that can be identified across scale and place in the earth, with the natural surroundings and the cultural environments produced by information technology included.[24] This was encapsulated in the motto "Survey before Program".[25] He saw cities as being changed by technology into more regional settlements, for which he coined the term conurbation.[26] Like to the garden city movement, he also believed in adding green areas to these urban regions.[26] The Regional Planning Clan of America advanced his ideas, coming upward with the 'regional city' which would take a variety of urban communities across a green landscape of farms, parks and wilderness with the assist of telecommunication and the auto.[27] This had major influence on the County of London Plan, 1944.[28]

City Beautiful motility [edit]

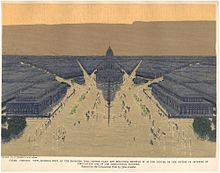

The Civic Centre Plaza planned (but never realized) in Burnham'due south plan for Chicago.

The City Beautiful movement was inspired by 19th century European capital cities such every bit Georges-Eugène Haussmann's Paris or the Vienna Ring Road.[29] An influential effigy was Daniel Burnham (1846-1912), who was the chief of structure of the World'southward Columbian Exposition in 1893.[29] Urban issues such as the 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago had created a perceived demand to reform the morality of the city amid some of the elites.[30] Burnham's greatest accomplishment was the Chicago program of 1909.[31] His aim was "to restore to the urban center a lost visual and aesthetic harmony, thereby creating the physical prerequisite for the emergence of a harmonious social order", essentially creating social reform through new slum clearance and creating public space, which also endeared it the support of the Progressivist motility.[32] This was too believed to exist economically advantageous past drawing in tourists and wealthy migrants.[32] Because of this it has been referred to every bit "trickle-down urban evolution" and equally "centrocentrist" for focusing simply on the core of the urban center.[33] Other major cities planned according to the movement principles included British colonial capitals in New Delhi, Harare, Lusaka Nairobi and Kampala,[34] [35] also as that of Canberra in Australia,[36] and Albert Speer's plan for the Nazi uppercase Germania.[37]

Towers in the park [edit]

Le Corbusier's Plan Voisin (1925) for Paris.

Le Corbusier (1887–1965) pioneered a new urban class called towers in the park. His arroyo was based on defining the house every bit 'a motorcar to live in'.[38] The Program Voisin he devised for Paris, which was never fulfilled, would accept involved the sabotage of much of celebrated Paris in favour of xviii compatible 700-pes belfry blocks.[39] Ville Contemporaine and the Ville Radieuse formulated his basic principles, including decongestion of the urban center by increased density and open up space by building taller on a smaller footprint.[39] Wide avenues should also be built to the city centre by demolishing old structures, which was criticized for lack of environmental awareness.[39] His generic ethos of planning was based on the rule of experts who would "work out their plans in full freedom from partisan pressures and special interests" and that "once their plans are formulated, they must be implemented without opposition".[xl] His influence on the Soviet Union helped inspire the 'urbanists' who wanted to build planned cities full of massive apartment blocks in Soviet countryside.[40] The merely urban center which he always really helped plan was Chandigarh in Republic of india.[41] Brasília, planned by Oscar Niemeyer, also was heavily influenced by his thought.[42] Both cities suffered from the upshot of unplanned settlements growing exterior them.[43]

Decentralised planning [edit]

Wright's sketches of Broadacre Urban center.

In the United States, Frank Lloyd Wright similarly identified vehicular mobility as a chief planning metric. Automobile-based suburbs had already been developed in the Land Club District in 1907-1908 (including later the earth's start car-based shopping centre of Country Society Plaza), as well as in Beverly Hills in 1914 and Palos Verdes Estates in 1923.[44] Wright began to idealise this vision in his Broadacre Urban center starting in 1924, with similarities to the garden city and regional planning movements.[45] The central idea was for technology to liberate individuals.[45] In his Usonian vision, he described the metropolis as

"spacious, well-landscaped highways, class crossings eliminated by a new kind of integrated by-passing or over- or under-passing all traffic in cultivated or living areas … Giant roads, themselves great architecture, pass public service stations . . . passing by farm units, roadside markets, garden schools, dwelling places, each on its acres of individually adorned and cultivated ground".[46]

This was justified as a democratic platonic, as ""Democracy is the ideal of reintegrated decentralization … many gratuitous units developing force as they learn by function and grow together in spacious mutual freedom."[46] This vision was however criticized past Herbert Muschamp as beingness contradictory in its call for individualism while relying on the chief-builder to blueprint it all.[46]

After World War Two, suburbs similar to Broadacre City spread throughout the US, merely without the social or economic aspects of his ideas.[47] A notable example was that of Levittown, built 1947 to 1951.[48] The suburban blueprint was criticized for their lack of form past Lewis Mumford as it lacked clear boundaries, and by Ian Nairn considering "Each building is treated in isolation, zip binds it to the next ane".[49]

In the Soviet Union too, the so-chosen deurbanists (such as Moisei Ginzburg and Mikhail Okhitovich) advocated for the apply of electricity and new transportation technologies (especially the machine) to disperse the population from the cities to the countryside, with the ultimate aim of a "townless, fully decentralized, and evenly populated country".[44] However, in 1931 the Communist Political party ruled such views every bit forbidden.[45]

Opposition to blueprint planning [edit]

Throughout both the United States and Europe, the rational planning movement declined in the latter half of the 20th century.[50] The reason for the motility's reject was also its strength. Past focusing and then much on a blueprint past technical elites, rational planning lost touch with the public it hoped to serve. Key events in this turn down in the U.s.a. include the sabotage of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis and the national backlash against urban renewal projects, particularly urban expressway projects.[51] An influential critic of such planning was Jane Jacobs, who wrote The Decease and Life of Smashing American Cities in 1961, claimed to be "one of the about influential books in the curt history of city planning".[52] She attacked the garden city movement because its "prescription for saving the city was to practice the city in" and because information technology "conceived of planning also as essentially paternalistic, if non disciplinarian".[52] The Corbusians on the other paw were claimed to be egoistic.[52] In dissimilarity, she dedicated the dense traditional inner-metropolis neighborhoods like Brooklyn Heights or Due north Embankment, San Francisco, and argued that an urban neighbourhood required nearly 200-300 people per acre, as well every bit a loftier cyberspace basis coverage at the expense of open up infinite.[53] She also advocated for a variety of land uses and building types, with the aim of having a abiding churn of people throughout the neighbourhood across the times of the day.[53] This substantially meant defending urban environments as they were earlier modern planning had aimed to start irresolute them.[53] As she believed that such environments were essentially cocky-organizing, her approach was effectively one of laissez-faire, and has been criticized for not existence able to guarantee "the evolution of good neighbourhoods".[54]

The most radical opposition was declared in 1969 in a manifesto on the New Lodge, with the words that:

The whole concept of planning (the town-and-country kind at to the lowest degree) has gone cockeyed … Somehow, everything must exist watched; nil must be allowed simply to "happen." No house can exist immune to be commonplace in the way that things just are commonplace: each projection must be weighed, and planned, and approved, and only and then built, and but afterwards that discovered to be commonplace after all.[55]

Some other course of opposition came from the advocacy planning movement, opposes to traditional superlative-downwardly and technical planning.[56]

Modernist planning [edit]

Cybernetics and modernism inspired the related theories of rational process and systems approaches to urban planning in the 1960s.[57] They were imported into planning from other disciplines.[57] The systems approach was a reaction to the bug associated with the traditional view of planning.[58] It did not understand the social and economic sides of cities, the complexity and interconnectedness of urban life, as well every bit lacking in flexibility.[58] The 'quantitative revolution' of the 1960s also created a bulldoze for more scientific and precise thinking, while the rise of ecology made the arroyo more natural.[59]

Systems theory [edit]

Systems theory is based on the formulation of phenomena as 'systems', which are themselves coherent entities equanimous of interconnected and interdependent parts.[60] A city can in this way be conceptualised as a system with interrelated parts of different land uses, connected past transport and other communications.[sixty] The aim of urban planning thereby becomes that of planning and controlling the system.[61] Similar ideas had been put forward by Geddes, who had seen cities and their regions equally analogous to organisms, though they did not receive much attention while planning was dominated by architects.[61]

The thought of the city as a system meant that it became disquisitional for planners to understand how cities functioned.[61] It likewise meant that a alter to one function in a urban center would have effects on others parts besides.[61] There were as well doubts raised about the goal of producing detailed blueprints of how cities should look similar in the finish, instead suggesting the need for more flexible plans with trajectories instead of stock-still futures.[62] Planning should also be an ongoing process of monitoring and taking action in the metropolis, rather than simply producing the pattern at i time.[62] The systems arroyo also necessitated taking into account the economical and social aspects of cities, across only the aesthetic and physical ones.[62]

Rational process arroyo [edit]

The focus on the procedural attribute of planning had already been pioneered by Geddes in his Survey-Assay-Program approach.[63] However, this arroyo had several shortfalls. It did not consider the reasons for doing a survey in the get-go place.[63] It also suggested that there should be simply a single plan to be considered.[63] Finally, information technology did not take into business relationship the implementation stage of the programme.[64] In that location should besides be further action in monitoring the outcomes of the plan after that.[64] The rational process, in contrast, identified five dissimilar stages: (one) the definition of issues and aims; (2) the identification of alternatives; (3) the evaluation of alternatives; (4) implementation: (v) monitoring.[64] This new approach represented a rejection of blueprint planning.[65]

Incrementalism [edit]

Beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, critiques of the rational paradigm began to emerge and formed into several dissimilar schools of planning thought. The kickoff of these schools is Lindblom's incrementalism. Lindblom describes planning as "muddling through" and idea that practical planning required decisions to be made incrementally. This incremental approach meant choosing from small number of policy approaches that tin can but take a small-scale number consequences and are firmly bounded by reality, constantly adjusting the objectives of the planning process and using multiple analyses and evaluations.[66]

Mixed scanning model [edit]

The mixed scanning model, developed by Etzioni, takes a similar, but slightly different approach. Etzioni (1968) suggested that organizations plan on two unlike levels: the tactical and the strategic. He posited that organizations could reach this by substantially scanning the environment on multiple levels and so choose different strategies and tactics to address what they found there. While Lindblom'southward approach only operated on the functional level Etzioni argued, the mixed scanning arroyo would let planning organizations to work on both the functional and more big-picture oriented levels.[67]

Political planning [edit]

In the 1960s, a view emerged of planning as an inherently normative and political activity.[68] Advocates of this approach included Norman Dennis, Martin Meyerson, Edward C. Banfield, Paul Davidoff, and Norton East. Long, the latter remarking that:

Plans are policies and policies, in a democracy at whatever rate, spell politics. The question is not whether planning volition reverberate politics simply whose politics it will reflect. What values and whose values will planners seek to implement? . . . No longer can the planner have refuge in the neutrality of the objectivity of the personally uninvolved scientist.[69]

The choices between culling end points in planning was a key result which was seen as political.[70]

Participatory planning [edit]

A public consultation event about urban planning in Helsinki

Participatory planning is an urban planning paradigm that emphasizes involving the entire community in the strategic and management processes of urban planning; or, community-level planning processes, urban or rural. It is often considered as part of customs development.[71] Participatory planning aims to harmonize views among all of its participants as well as prevent conflict betwixt opposing parties. In addition, marginalized groups have an opportunity to participate in the planning process.[72]

Patrick Geddes had first advocated for the "real and active participation" of citizens when working in the British Raj, arguing against the "Dangers of Municipal Government from above" which would cause "disengagement from public and popular feeling, and consequently, before long, from public and pop needs and usefulness".[73] Further on, cocky-build was researched by Raymond Unwin in the 1930s in his Town Planning in Do.[74] The Italian agitator architect Giancarlo De Carlo and then argued in 1948 that ""The housing trouble cannot exist solved from in a higher place. It is a trouble of the people, and information technology will not be solved, or even boldly faced, except by the physical will and action of the people themselves", and that planning should exist "as the manifestation of communal collaboration".[75] Through the Architectural Association School of Architecture, his ideas defenseless John Turner, who started working in Peru with Eduardo Neira.[75] He would continue working in Lima from the mid-'50s to the mid-'60s.[76] In that location he establish that the barrios were not slums, but were rather highly organised and well-performance.[77] Equally a event, he came to the conclusion that:

"When dwellers command the major decisions and are costless to make their ain contributions in the design, construction or management of their housing, both this procedure and the environs produced stimulate individual and social well-being. When people have no control over nor responsibility for key decisions in the housing process, on the other hand, dwelling house environments may instead go a barrier to personal fulfillment and a burden on the economy."[78]

The function of the government was to provide a framework within which people would be able to piece of work freely, for example by providing them the necessary resources, infrastructure and country.[78] Self-build was afterward again taken upward past Christopher Alexander, who led a projection chosen People Rebuild Berkeley in 1972, with the aim to create "self-sustaining, self-governing" communities, though it concluded up being closer to traditional planning.[79]

Synoptic planning [edit]

Subsequently the "fall" of blueprint planning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the synoptic model began to emerge as a ascendant strength in planning. Lane (2005) describes synoptic planning as having four cardinal elements:

- "(i) an enhanced emphasis on the specification of goals and targets; (two) an emphasis on quantitative analysis and predication of the surround; (3) a concern to identify and evaluate alternative policy options; and (4) the evaluation of means confronting ends (page 289)."[80]

Public participation was kickoff introduced into this model and information technology was by and large integrated into the arrangement procedure described above. All the same, the trouble was that the thought of a single public interest nevertheless dominated attitudes, finer devaluing the importance of participation because it suggests the thought that the public interest is relatively easy to notice and just requires the virtually minimal form of participation.[lxxx]

Transactive planning [edit]

Transactive planning was a radical break from previous models. Instead of considering public participation equally a method that would be used in addition to the normal training planning process, participation was a central goal. For the first time, the public was encouraged to take on an active part in the policy-setting procedure, while the planner took on the role of a distributor of information and a feedback source.[fourscore] Transactive planning focuses on interpersonal dialogue that develops ideas, which will exist turned into activeness. One of the primal goals is common learning where the planner gets more data on the community and citizens to become more than educated about planning issues.[81]

Advocacy planning [edit]

Formulated in the 1960s by lawyer and planning scholar Paul Davidoff, the advancement planning model takes the perspective that there are large inequalities in the political organisation and in the bargaining process betwixt groups that outcome in large numbers of people unorganized and unrepresented in the process. It concerns itself with ensuring that all people are equally represented in the planning process by advocating for the interests of the underprivileged and seeking social change.[82] [83] Once more, public participation is a fundamental tenet of this model. A plurality of public interests is assumed, and the role of the planner is substantially the one as a facilitator who either advocates directly for underrepresented groups direct or encourages them to become part of the procedure.[80]

Radical planning [edit]

Radical planning is a stream of urban planning which seeks to manage development in an equitable and community-based manner. The seminal text to the radical planning movement is Foundations for a Radical Concept in Planning (1973), past Stephen Grabow and Allen Heskin. Grabow and Heskin provided a critique of planning equally elitist, centralizing and change-resistant, and proposed a new paradigm based upon systems modify, decentralization, communal guild, facilitation of human development and consideration of ecology. Grabow and Heskin were joined by Head of Section of Town Planning from the Polytechnic of the Southward Banking concern Shean McConnell, and his 1981 work Theories for Planning.

In 1987 John Friedmann entered the fray with Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action, promoting a radical planning model based on "decolonization", "democratization", "self-empowerment" and "reaching out". Friedmann described this model as an "Agropolitan development" paradigm, emphasizing the re-localization of primary production and manufacture. In "Toward a Non-Euclidian Manner of Planning" (1993) Friedmann further promoted the urgency of decentralizing planning, advocating a planning paradigm that is normative, innovative, political, transactive and based on a social learning arroyo to cognition and policy.

Bargaining model [edit]

The bargaining model views planning every bit the issue of giving and take on the part of a number of interests who are all involved in the process. It argues that this bargaining is the all-time manner to bear planning within the bounds of legal and political institutions.[84] The well-nigh interesting function of this theory of planning is that it makes public participation the key dynamic in the controlling process. Decisions are fabricated first and foremost by the public, and the planner plays a more than small-scale part.[80]

Communicative approach [edit]

The communicative approach to planning is perhaps the near difficult to explicate. It focuses on using communication to assistance different interests in the process to understand each other. The idea is that each individual will approach a conversation with his or her own subjective feel in heed and that from that conversation shared goals and possibilities will emerge. Once more, participation plays a key part in this model. The model seeks to include a broad range of voice to enhance the debate and negotiation that is supposed to grade the core of actual programme making. In this model, participation is actually fundamental to the planning process happening. Without the involvement of concerned interests, there is no planning.[80] Bent Flyvbjerg and Tim Richardson have developed a critique of the chatty approach and an culling theory based on an agreement of power and how information technology works in planning.[85] [86] Looking at each of these models it becomes articulate that participation is not only shaped by the public in a given area or by the attitude of the planning organization or planners that piece of work for information technology. In fact, public participation is largely influenced by how planning is defined, how planning problems are defined, the kinds of knowledge that planners choose to employ and how the planning context is set.[80] Though some might argue that is too hard to involve the public through transactive, advocacy, bargaining and chatty models because transportation is some ways more technical than other fields, information technology is important to notation that transportation is perhaps unique among planning fields in that its systems depend on the interaction of a number of individuals and organizations.[87]

Procedure [edit]

Blight may sometimes cause communities to consider redeveloping and urban planning.

Changes to the planning procedure [edit]

Strategic Urban Planning over past decades take witnessed the metamorphosis of the role of the urban planner in the planning process. More citizens calling for democratic planning & evolution processes accept played a huge function in allowing the public to make important decisions every bit part of the planning procedure. Community organizers and social workers are at present very involved in planning from the grassroots level.[88] The term advancement planning was coined by Paul Davidoff in his influential 1965 newspaper, "Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning" which acknowledged the political nature of planning and urged planners to acknowledge that their deportment are non value-neutral and encouraged minority and underrepresented voices to be part of planning decisions.[89] Benveniste argued that planners had a political role to play and had to bend some truth to ability if their plans were to be implemented.[90]

Developers have also played huge roles in evolution, particularly by planning projects. Many recent developments were results of big and small-scale developers who purchased land, designed the district and synthetic the evolution from scratch. The Melbourne Docklands, for example, was largely an initiative pushed by private developers to redevelop the waterfront into a high-cease residential and commercial district.

Recent theories of urban planning, espoused, for case past Salingaros see the city equally an adaptive organisation that grows co-ordinate to procedure similar to those of plants. They say that urban planning should thus take its cues from such natural processes.[91] Such theories besides abet participation by inhabitants in the design of the urban environment, every bit opposed to simply leaving all development to large-scale construction firms.[92]

In the process of creating an urban program or urban pattern, carrier-infill is one mechanism of spatial organization in which the city'due south figure and ground components are considered separately. The urban figure, namely buildings, is represented as total possible building volumes, which are left to be designed by architects in the following stages. The urban footing, namely in-between spaces and open up areas, are designed to a higher level of item. The carrier-infill approach is defined past an urban design performing as the carrying structure that creates the shape and scale of the spaces, including future edifice volumes that are then infilled by architects' designs. The contents of the carrier structure may include street pattern, landscape compages, open space, waterways, and other infrastructure. The infill structure may contain zoning, building codes, quality guidelines, and Solar Access based upon a solar envelope.[93] [94] Carrier-Infill urban design is differentiated from complete urban blueprint, such every bit in the monumental axis of Brasília, in which the urban pattern and compages were created together.

In carrier-infill urban design or urban planning, the negative infinite of the city, including landscape, open space, and infrastructure is designed in particular. The positive space, typically edifice a site for future construction, is only represented in unresolved volumes. The volumes are representative of the full possible building envelope, which tin and so be infilled by individual architects.

See also [edit]

- Index of urban planning articles

- Alphabetize of urban studies articles

- List of planned cities

- List of planning journals

- List of urban planners

- List of urban theorists

- MONU – magazine on urbanism

- Planetizen

- Transition Towns (network)

- Transportation demand direction

- Urban acupuncture

- Urban vitality

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ "How Planners Utilize Planning Theory". Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ James, Paul; Holden, Million; Lewin, Mary; Neilson, Lyndsay; Oakley, Christine; Truter, Art; Wilmoth, David (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Mieg, Harald; Töpfer, Klaus (eds.). Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Evolution. Routledge.

- ^ Van Assche, Kristof; Beunen, Raoul; Duineveld, Martijn; de Jong, Harro (eighteen September 2012). "Co-evolutions of planning and blueprint: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems". Planning Theory. 12 (two): 177–198. doi:10.1177/1473095212456771. S2CID 109970261.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. three. ISBN978-1-118-45651-iv.

- ^ Wheeler, Stephen (2004). "Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities", Routledge; 3rd edition.[ page needed ]

- ^ "Why Sustainable Architecture Is Condign more Of import | CRL". c-r-50.com . Retrieved xix May 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 4. ISBN978-ane-84920-677-8.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. pp. 4–5, 13. ISBN978-1-84920-677-viii.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 15. ISBN978-1-84920-677-eight.

- ^ Hall, Peter (2008). The Cities of Tomorrow. Publishing: Blackwell. pp. 13–47, 87–141. ISBN978-0-631-23252-0.

- ^ Hall, Peter (2008). The Cities of Tomorrow. Publishing: Blackwell. pp. 48–86. ISBN978-0-631-23252-0.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 90. ISBN978-ane-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 91. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 92–96. ISBN978-1-118-45651-iv.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 96. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 97. ISBN978-i-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 98. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 255. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link) - ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City . Routledge. pp. 621. ISBN9780415252256.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 150. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 152. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 154. ISBN978-one-118-45651-iv.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 154–155. ISBN978-i-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 155. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 161. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 165. ISBN978-1-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 196. ISBN978-i-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN978-ane-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 204. ISBN978-i-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 204. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 207. ISBN978-i-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 210–211. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 212. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 218. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 223. ISBN978-i-118-45651-iv.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 229. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 238. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 241. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 244. ISBN978-ane-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 245. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 248–249. ISBN978-1-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 251. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 340–341. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 342. ISBN978-i-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 344–345. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 346. ISBN978-i-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 351. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 353–354. ISBN978-i-118-45651-iv.

- ^ Allmendinger, Philip (2002). Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory . Routledge. pp. 20–25.

- ^ Black, William R. Transportation: A Geographical Analysis. The Guilford1 Press. p. 29.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 282. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b c Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 283. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 284. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 312. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 315. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Taylor, Nigel (eleven June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. threescore. ISBN978-ane-84920-677-viii.

- ^ a b Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 64. ISBN978-ane-84920-677-8.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 65. ISBN978-1-84920-677-8.

- ^ a b Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 61. ISBN978-i-84920-677-eight.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 62. ISBN978-1-84920-677-viii.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 63. ISBN978-1-84920-677-8.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 66. ISBN978-1-84920-677-8.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Nigel (xi June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 67. ISBN978-1-84920-677-viii.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 69. ISBN978-1-84920-677-8.

- ^ Lindblom, Charles Eastward. (undefined NaN). "The Scientific discipline of 'Muddling Through'". Public Administration Review. 19 (2): 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677. JSTOR 973677.

- ^ Etzioni, A. (1968). The active gild: a theory of societal and political processes. New York: Free Press.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 77. ISBN978-ane-84920-677-8.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. p. 83. ISBN978-1-84920-677-viii.

- ^ Taylor, Nigel (11 June 1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. SAGE. pp. 83–84. ISBN978-1-84920-677-8.

- ^ Lefevre, Pierre; Kolsteren, Patrick; De Wael, Marie-Paule; Byekwaso, Francis; Beghin, Ivan (December 2000). "Comprehensive Participatory Planning and Evaluation" (PDF). Antwerp, Kingdom of belgium: IFAD. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ McTague, Colleen; Jakubowski, Susan (October 2013). "Marching to the vanquish of a silent pulsate: Wasted consensus-building and failed neighborhood participatory planning". Applied Geography. 44: 182–191. doi:ten.1016/j.apgeog.2013.07.019.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 299. ISBN978-one-118-45651-iv.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 Apr 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Blueprint Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 300. ISBN978-ane-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 301. ISBN978-1-118-45651-four.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 302. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Pattern Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 304. ISBN978-1-118-45651-4.

- ^ a b Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 305–306. ISBN978-one-118-45651-4.

- ^ Hall, Peter (17 April 2014). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. p. 311. ISBN978-1-118-45651-iv.

- ^ a b c d due east f grand Lane, Marcus B. (Nov 2005). "Public Participation in Planning: an intellectual history". Australian Geographer. 36 (3): 283–299. doi:10.1080/00049180500325694. S2CID 18008094.

- ^ Friedman, J. (1973). Retracking America: A Theory of Transactive Planning. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

- ^ Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. Periodical of the American Institute of Planners, 31 (4), 331–338.

- ^ Mazziotti, D. F. (1982). The underlying assumptions of advocacy planning: pluralism and reform. In C. Paris (Ed.), Disquisitional readings in planning theory (pp. 207–227) New York: Pergamon Press.

- ^ McDonald, One thousand. T. (1989). Rural Country Employ Planning Decisions by Bargaining. Journal of Rural Studies, 5 (4), 325–335.

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Aptitude, 1996, "The Dark Side of Planning: Rationality and Realrationalität", in Seymour J. Mandelbaum, Luigi Mazza, and Robert Due west. Burchell, eds., Explorations in Planning Theory. New Brunswick, NJ: Heart for Urban Policy Research Press, pp. 383–394.

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Aptitude and Tim Richardson, 2002, "Planning and Foucault: In Search of the Night Side of Planning Theory." In Philip Allmendinger and Marker Tewdwr-Jones, eds., Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 44–62.

- ^ Wachs, M. (2004). Reflections on the planning process. In South. Hansen, & G. Guliano (Eds.), The Geography of Urban Transportation (3rd Edition ed., pp. 141–161). The Guilford Press.

- ^ Forester John. "Planning in the Face up of Conflict", 1987, ISBN 0-415-27173-8, Routledge, New York.

- ^ "Advocacy and Community Planning: Past, Present, and Future". Planners Network. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Benveniste, Guy (1994). Mastering the Politics of Planning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ ""Life and the geometry of the environment", Nikos Salingaros, November 2010" (PDF) . Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ ""P2P Urbanism", collection of articles by Nikos Salingaros and others" (PDF).

- ^ Capeluto, I.Thou.; Shaviv, Due east. (2001). "On the use of 'solar volume' for determining the urban material". Solar Energy. 70 (iii): 275–280. Bibcode:2001SoEn...seventy..275C. doi:10.1016/S0038-092X(00)00088-viii.

- ^ Nelson, Nels O. Planning the Productive City, 2009, accessed 30 Dec 2010.

[1] Bibliography

- Allmendinger, Phil; Gunder, Michael (11 August 2016). "Applying Lacanian Insight and a Nuance of Derridean Deconstruction to Planning's 'Dark Side'". Planning Theory. 4 (ane): 87–112. doi:10.1177/1473095205051444. S2CID 145100234.

- Bogo, H.; Gómez, D.R.; Reich, Southward.50.; Negri, R.Yard.; San Román, Eastward. (Apr 2001). "Traffic pollution in a downtown site of Buenos Aires Urban center". Atmospheric Environment. 35 (10): 1717–1727. Bibcode:2001AtmEn..35.1717B. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00555-0.

- Garvin, Alexander (2002). The American Metropolis: What Works and What Doesn't. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN978-0-07-137367-viii. (A standard text for many college and graduate courses in city planning in America)

- Dalley, Stephanie, 1989, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford World's Classics, London, pp. 39–136

- Gunder, Michael (October 2003). "Passionate planning for the others' want: an agonistic response to the dark side of planning". Progress in Planning. threescore (3): 235–319. doi:x.1016/S0305-9006(02)00115-0.

- Hoch, Charles, Linda C. Dalton and Frank South. And so, editors (2000). The Practice of Local Government Planning, Intl Urban center County Direction Assn; 3rd edition. ISBN 0-87326-171-2 (The "Green Book")

- James, Paul; Holden, One thousand thousand; Lewin, Mary; Neilson, Lyndsay; Oakley, Christine; Truter, Art; Wilmoth, David (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg and Klaus Töpfer (ed.). Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Evolution. Routledge.

- Kemp, Roger L. and Carl J. Stephani (2011). "Cities Going Green: A Handbook of Best Practices." McFarland and Co., Inc., Jefferson, NC, United states of america, and London, England, Uk. ISBN 978-0-7864-5968-1.

- Oke, T. R. (January 1982). "The energetic footing of the urban heat island". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 108 (455): i–24. Bibcode:1982QJRMS.108....1O. doi:10.1002/qj.49710845502.

- Pløger, John (30 November 2016). "Public Participation and the Art of Governance". Environs and Planning B: Planning and Design. 28 (two): 219–241. doi:10.1068/b2669. S2CID 143996926.

- Roy, Ananya (March 2008). "Post-Liberalism: On the Ethico-Politics of Planning". Planning Theory. seven (i): 92–102. doi:10.1177/1473095207087526. S2CID 143458706.

- Santamouris, Matheos (2006). Environmental Design of Urban Buildings: An Integrated Approach.

- Shrady, Nicholas, The Final Solar day: Wrath, Ruin & Reason in The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, Penguin, 2008, ISBN 978-0-14-311460-4

- Tang, Wing-Shing (17 August 2016). "Chinese Urban Planning at L: An Assessment of the Planning Theory Literature". Periodical of Planning Literature. fourteen (3): 347–366. doi:ten.1177/08854120022092700. S2CID 154281106.

- Tunnard, Christopher and Boris Pushkarev (1963). Human being-Made America: Anarchy or Command?: An Inquiry into Selected Problems of Design in the Urbanized Landscape, New Haven: Yale University Press. (This book won the National Book Accolade, strictly America; a time capsule of photography and pattern arroyo.)

- Wheeler, Stephen (2004). "Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities", Routledge; 3rd edition.

- Yiftachel, Oren, 1995, "The Night Side of Modernism: Planning every bit Control of an Ethnic Minority," in Sophie Watson and Katherine Gibson, eds., Postmodern Cities and Spaces (Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell), pp. 216–240.

- Yiftachel, Oren (6 November 2016). "Planning and Social Control: Exploring the Dark Side". Periodical of Planning Literature. 12 (iv): 395–406. doi:10.1177/088541229801200401. S2CID 14859857.

- Yiftachel, Oren (11 August 2016). "Essay: Re-engaging Planning Theory? Towards 'South-Eastern' Perspectives". Planning Theory. v (3): 211–22. doi:x.1177/1473095206068627. S2CID 145359885.

- A Brusk Introduction to Radical Planning Theory and Practice, Doug Aberley Ph.D. MCIP, Winnipeg Inner City Research Alliance Summer Institute, June 2003

- McConnell, Shean. Theories for Planning, 1981, David & Charles, London.

Further reading [edit]

- Urban Planning, 1794–1918: An International Anthology of Articles, Briefing Papers, and Reports, Selected, Edited, and Provided with Headnotes by John W. Reps, Professor Emeritus, Cornell University.

- City Planning According to Creative Principles, Camillo Sitte, 1889

- Missing Eye Housing: Responding to the Demand for Walkable Urban Living by Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design, Inc., 2012

- Kemp, Roger 50. and Carl J. Stephani (2011). "Cities Going Light-green: A Handbook of All-time Practices." McFarland and Co., Inc., Jefferson, NC, United states of america, and London, England, Great britain. (ISBN 978-0-7864-5968-one).

- Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, Ebenezer Howard, 1898

- The Improvement of Towns and Cities, Charles Mulford Robinson, 1901

- Town Planning in practice, Raymond Unwin, 1909

- The Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick Winslow Taylor, 1911

- Cities in Evolution, Patrick Geddes, 1915

- The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch, 1960

- The Concise Townscape, Gordon Cullen, 1961

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, 1961

- The City in History, Lewis Mumford, 1961

- The City is the Frontier, Charles Abrams, Harper & Row Publishing, New York, 1965.

- A Pattern Linguistic communication, Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein, 1977

- What Practise Planners Practice?: Power, Politics, and Persuasion, Charles Hoch, American Planning Clan, 1994. ISBN 978-0-918286-91-8

- Planning the Twentieth-Century American Urban center, Christopher Silver and Mary Corbin Sies (Eds.), Johns Hopkins Academy Press, 1996

- "The Metropolis Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History", Spiro Kostof, second Edition, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1999 ISBN 978-0-500-28099-7

- The American City: A Social and Cultural History, Daniel J. Monti, Jr., Oxford, England and Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1999. 391 pp. ISBN 978-1-55786-918-0.

- Urban Development: The Logic Of Making Plans, Lewis D. Hopkins, Island Press, 2001. ISBN i-55963-853-two

- 'Readings in Planning Theory, fourth edition, Susan Fainstein and James DeFilippis, Oxford, England and Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 2016.

- Taylor, Nigel, (2007), Urban Planning Theory since 1945, London, Sage.

- Planning for the Unplanned: Recovering from Crises in Megacities, by Aseem Inam (published past Routledge U.s., 2005).

External links [edit]

- Urban and Regional Planning at Curlie

- ^ Buchan, Robert (fourteen November 2019). "Transformative Incrementalism: Planning for transformative modify in local nutrient systems". Progress in Planning. 134: 100424. doi:x.1016/j.progress.2018.07.002.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theories_of_urban_planning

0 Response to "thomas whately advocated a natural approach to landscape design using what four basic elements?"

Post a Comment